Work ethic fueled Gardner after college snub

Brett Gardner is not a typical Yankees slugger, although his surprising home run power last season points to a trend -- some would even call it a mission -- that began a decade ago.

"I just remember getting to the field early. I'd get there around noon for a 7 p.m. game and it wouldn't be long before little Gardy comes walking into the clubhouse," recalled Andy Stankiewicz. "He was there, he was just so focused. This is what he wanted to do, and he did it."

Stankiewicz, who made his Major League debut with the Yankees in 1992, was Gardner's first professional manager after the 21-year-old outfielder from South Carolina was drafted by New York in 2005.

"He was a little bulldog in the way he approached the game," Stankiewicz said.

But long before Gardner arrived at a tiny ballpark in Staten Island, New York, he was a 17-year-old kid with the goal of playing college baseball. One of 26 aspiring players, Gardner -- not recruited in high school -- tried out for the College of Charleston as a walk-on.

He didn't make the cut.

So the legends goes, Gardner was aided by a late-night letter penned by his father, Jerry, who'd reached Double-A with the Phillies. Gardner got a second chance at his career several days later when Charleston's coach, moved by the note, invited the outfielder to show up for practice, with no guarantee of sticking around.

Gardner, at 5-foot-10 and 135 pounds, didn't leave the team again until the Yankees selected him in the third round of the Draft four years later.

"If I was a coach, I'd be like, 'This kid's not going to cut it,'" Gardner told The New York Times in 2009 of his failed tryout at Charleston. "I was fortunate enough to get called back several weeks later to work out with the team, and it ended up working out."

Gardner's story is rare and heartwarming, a tale that countless Little Leaguers and high school kids believe can be their path to the Majors some day. He was a thin, speedy outfielder with no power, and yet last year, he at times led the historically high-powered Yankees in homers and stolen bases.

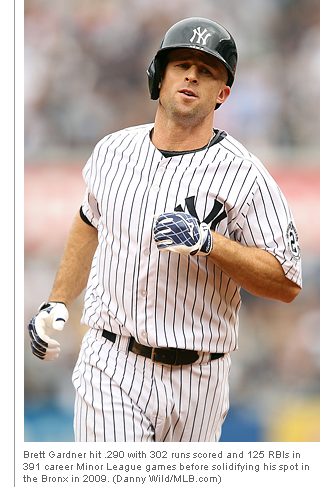

Brett Gardner, a walk-on, was the College of Charleston's highest-drafted player in the school's history. (Danny Wild/MLB.com)

|

Gardner joined the Yankees after the organization scouted him as a senior, when he led all of college baseball in hits. He began his pro career in 2005 in Staten Island, a few miles and a ferry ride away from Yankee Stadium. There, he helped the Baby Bombers go 52-24 and claim the New York-Penn League championship under Stankiewicz, a former infielder who spent the first two of his seven big league seasons with New York.

Gardner, who went 2-for-4 with a run scored in the Yankees' 3-2 walk-off win over Auburn to win the crown that September, batted .284 on a team that included five other future Major Leaguers, most notably infielder Eduardo Nunez, who reached the Bronx a year after Gardner helped the Yankees to the 2009 World Series.

Stankiewicz recalled Gardner's attitude, one of a player who hadn't forgotten about being snubbed in college. He had something to prove in every at-bat.

"His ability to run was the difference-maker, he really got down the line. I think he turned himself into a baseball player, not that he wasn't back then, but he's always had that mentality, a tough kid, no nonsense, 'Yes sir, no sir,'" Stankiewicz said. "He was a guy who was the first one to the park, last one to leave. Always pretty focused on his career. He wasn't, 'Hey, I'm going to try to do this -- I'm in this for the long haul.' I think that's how it's played out. He's turned himself into a pivotal part of the Yankees' success."

Gardner helped Double-A Trenton claim the Eastern League's Northern Division title in 2006 after starting the season with Class A Advanced Tampa. In 118 games that year, he batted .298 with 24 extra-base hits, 35 RBIs and 58 stolen bases.

Bill Masse, now the Mariners' eastern scouting supervisor, managed Gardner with the Thunder that season.

|

|

| "He's a coach's dream no one's gonna outwork Brett Gardner, period -- that's the bottom line. He made himself into an above average Major Leaguer. He's a great example for a lot of kids to follow." |

-- Bill Masse |

|

|

"The one word that comes to mind is 'determination,' period," Masse said. "The guy could always fly. He's the fastest kid I've ever coached -- always willing to learn and willing to take any information I gave him or any coaches gave him. He was a coach's dream. His work ethic and determination was off the charts."

Gardner's gritty attitude made coaches smile and kept him on the right path.

"Brett Gardner is a true baseball lifer, that's what he is," Masse added. "He's that guy that, even being a third-round pick, he's just a classic, gritty baseball gamer. He made himself into what he is. He's a great example for kids that love baseball. He had the speed, which a lot of kids don't, a lot of guys don't -- Dustin Pedroia is someone similar, without the speed. But Brett could fly -- he had that advantage going for him."

Stankiewicz agreed about Gardner's mission to grind through pain and setbacks.

"He's a great worker and has great work ethic," Stankiewicz said. "A real professional, he just went about his business, a tough kid. That year he had some growing problems -- he tried to work from his college season to his pro season, but he wanted nothing to do with not playing. He didn't care what his body felt like, he wanted to play every day.

"He had a chip on his shoulder, for sure. He'd tell you, that's one of the things that's made him good. That chip, 'I'm gonna prove people wrong.' That's part of it, believing in yourself when a lot of people don't: 'I'm gonna show you.' And so when he got there, you could just tell he was very good."

Gardner hit five homers in his first season with Staten Island but just one over the next two years, raising some concern as to whether an outfielder without power could start for the Yankees in the Bronx.

"I remember [Minor League coach] Gary Denbo telling me that this guy will play center field for the New York Yankees some day. And people in the industry didn't see it," Yankees general manager Brian Cashman told the Wall Street Journal last summer. "I remember one person said Mickey Mantle will roll over in his grave if Gardy plays center field."

Fine-tuning Gardner's swing and approach was something the organization worked on at Trenton, Masse said. Both he and Stankiewicz agreed that Gardner had the skills, but it was his work ethic that put him over the top.

"The guy obviously had the tools of speed and he obviously could play defense, but he had to work on hitting. Even today, he'll tell you know his swing is stiff. He's had to work on really concentrating on flexibility in his swing, and he's done that," Masse said. "This is a guy who was really hard on himself and he matured and became a better player. He's a coach's dream -- no one's gonna outwork Brett Gardner, period, that's the bottom line. ... He's a great example for a lot of kids to follow."

Gardner possessed upside that the Yankees' roster, full of veteran sluggers, has recently lacked: youth, speed and athleticism. He stole 58 bases in 2006 and 39 the following year, which he split between Trenton and Triple-A Scranton Wilkes/Barre. In 2008, bulked up to 185 pounds, he combined for 50 steals while reaching the Majors in mid-August.

Masse said he isn't surprised that Gardner's power has grown in the Majors despite facing better pitching.

"He's always had pull power. You're not going to see Brett hit a ball out of left-center, but he'll hit it to the pull side, especially at Yankee Stadium," Masse said. "He's always had that power to the pull side, always a guy that needed to find his swing. I grew up as a hitting guy myself, I really studied it, and [Gardner] was always taught to use his speed, hit the ball on the ground and run. I was a big believer in telling him all the time to swing the bat like you can swing it. Don't worry about hitting the ball on the ground, don't worry about beating out hits, just hit line drives -- let the rest take care of itself."

It was that coaching that helped Gardner, who went homerless in 118 games in 2006, see hitting from a different perspective.

"The first time I got him was in Double-A, he was kind of like that guy who we had to retool his swing a little it to get back to using his natural ability rather than swinging based on speed. And once he did that, you started to see his power," Masse said. "It takes some time to develop that kind of power. We taught him to use his speed, but he started to realize, 'I can hit the ball out of the park.' I think that's when he started to hit for more power."

Brett Gardner worked his way up through Tampa, Trenton and Scranton/Wilkes-Barre. (Photos: Joy Absalon, Kevin Pataky, Mike Janes)

|

Stankiewicz, now the head coach at Grand Canyon University in Arizona, also saw Gardner's potential.

"Brett, he was a little guy, but he was strong. I think this past year, I think he hit almost 20 [homers]. He was finding his swing a little bit. You made a mistake in and he made you pay," said Stankiewicz. "It's a process, it takes a little time. It doesn't surprise me that he's learned how to see the whole field."

All of Gardner's 17 homers in 2014 came out of the leadoff spot, but Yankees manager Joe Girardi was comfortable moving him around the lineup -- Gardner actually hit third in 10 games and belted the milestone 15,000th homer in Yankees history.

"I think players have it, but I think they learn how to use it better," Girardi said. "And some years guys just get more pitches to hit out of the ballpark, but I've always felt that he could hit double digits.

"I just think [he's] maturing as a ballplayer," Girardi added. "Understanding what he's capable of doing and probably being healthy is the biggest thing, and feeling pretty good during the course of the season, most of the year."

Following Derek Jeter's retirement, Gardner is the most accomplished everyday Yankee who came through the farm system. He signed a four-year, $52 million extension last year and is being promoted by the Yankees' as the "Face of MLB" on social media this offseason.

The success may have never come without that letter from his father while Gardner was in college. Last July, he tagged Rangers ace Yu Darvish for two homers.

"I just blame the parents of Brett Gardner," Darvish said. "I just blame them for creating a great hitter."

Danny Wild is an editor for MiLB.com. Follow his MLBlog column, Minoring in Twitter.

These 15 moments led to season No. 15 of Minor League road trips

Benjamin Hill travels the nation collecting stories about what makes Minor League Baseball unique. This excerpt from his newsletter is a mere taste of the smorgasbord of delights he offers every week. Read the full newsletter here, and subscribe to his newsletter here.

MiLB podcast crew makes Opening Day predictions

Check out the latest episodes of The Show Before the Show, MiLB.com's official podcast. A segment rundown is listed below, in case you want to skip to a particular section. Like the podcast? Subscribe, rate and review on Apple Podcasts. The podcast is also available via Spotify, Megaphone and other

Everything you need to know for Triple-A Opening Day

First, there was big league Opening Day. Now it's Triple-A's turn to take the spotlight. The Minor League season opens Friday when the Triple-A International League and Pacific Coast League seasons get underway for the first of MiLB’s two Opening Days. And right out of the gates, several of baseball's

Top prospects to watch at Triple-A -- one for each organization

It’s Triple-A’s turn up to bat on Friday. The regular season begins for the Minor Leagues’ highest level one day after the action starts on the Major League side. Fun fact: it’ll be the earliest start to a Minor League season since 1951 (March 27). Double-A, High-A and Single-A will

Here's where every Top 100 prospect is expected to start the season

The 2025 Opening Day prospect roster announcements began last week when the Cubs informed Matt Shaw (MLB No. 19) he was making the trip overseas to compete in the Tokyo Series. Roki Sasaki (No. 1) also received the good news, but his assignment was much less of a surprise. Now

Nationals prospect King joins MiLB podcast

Check out the latest episodes of The Show Before the Show, MiLB.com's official podcast. A segment rundown is listed below, in case you want to skip to a particular section. Like the podcast? Subscribe, rate and review on Apple Podcasts. The podcast is also available via Spotify, Megaphone and other

Here are the 2025 All-Spring Breakout Teams

Fifteen games, several jersey swaps and countless highlights later, the second edition of Spring Breakout has officially concluded – and it lived up to its billing. Of the 16 contests sprinkled across four days, only one game (Dodgers vs. Cubs) was rained out. Coincidentally, the Cubs were one of two

Rox young sluggers aim to bring pop back to Coors Field

SCOTTSDALE, Ariz. -- Coors Field may provide the best run-scoring environment in Major League Baseball, but the Rockies haven’t taken advantage of it in recent years. Even without adjusting for Coors, they have fielded offenses worse than the league average the past three seasons, and they scored the fewest runs

Astros brass sees potential in consistently 'underranked' farm system

WEST PALM BEACH, Fla. -- The last time the Astros landed in the top 10 of MLB Pipeline’s farm system rankings was before the 2019 season. Since those rankings expanded to all 30 teams ahead of the 2020 season -- 11 lists in total -- they’ve never ranked higher than

Complete results and highlights from Spring Breakout

The second edition of MLB Spring Breakout is complete, and there was no shortage of highlights from the future stars of Major League Baseball over the four-day showcase. Here's a complete breakdown of the 16-game exhibition:

Southpaw Spring Breakout: White Sox future on display with Schultz, Smith

GLENDALE, Ariz. -- If all goes as planned for the White Sox, left-handers Hagen Smith and Noah Schultz won’t spend much time following each other to the mound in a single game. Schultz, the No. 1 White Sox prospect and No. 16 overall, per MLB Pipeline, and Smith, who is

In first pro game, Rainer offers pop, promise to Tigers fans

NORTH PORT, Fla. -- Bryce Rainer’s pro career consisted of workouts and batting practice until Sunday.

'Me and Brady on the dirt again': House, King reunite at Spring Breakout

WEST PALM BEACH, Fla. -- The 2025 Spring Breakout was a flashback for Brady House and Seaver King. Over 10 years ago, the infielders were travel ball teammates in Georgia who shared the dream of making it to the Major Leagues. Now, they are top prospects in the same organization,

Lambert -- 'an adrenaline guy' -- hoping to be next Mets bullpen gem

WEST PALM BEACH, Fla. -- Ryan Lambert loves throwing hard. He relishes the idea of getting to two strikes and blowing hitters away. “Get me in a game,” Lambert said, “cool things will happen.”

Stewart embraces Spring Breakout: 'What's not to love?'

PHOENIX -- Sal Stewart was one fired-up Reds prospect. On Sunday in the first inning during the organization's 9-7 Spring Breakout win over Brewers prospects, Stewart lifted a 2-2 pitch that sailed over the center fielder's head to the wall. Already not known as a speedster, he stumbled running between

Prospect Peña quietly drawing raves in Brewers' farm system

PHOENIX – Jesús Made was at the top of the Brewers’ lineup for Sunday’s 9-7 loss to the Reds in the finale of MLB’s four-day Spring Breakout, a fitting perch when you consider that the 17-year-old infielder is under a bright spotlight as MLB Pipeline’s No. 55 prospect. Made could

Brecht -- in 1st outing since '24 Draft -- wows at Spring Breakout

GLENDALE, Ariz. -- Sunday's Spring Breakout showcase was the perfect unveiling for Rockies No. 5 prospect Brody Brecht. A right-handed pitcher from the University of Iowa whom the Rockies selected 38th overall last summer, Brecht had a nice collegiate resume, an interesting backstory as a former wide receiver for the

Braves prospects show promise in Spring Breakout

NORTH PORT, Fla. -- As Terry Pendleton prepared to serve as the manager of the Braves prospect team that played the Tigers prospect team in a Spring Breakout game on Sunday afternoon, he said fans should be patient with John Gil and Luis Guanipa, a pair of teenagers who have

Yanks' Lagrange flashes triple-digit heat in Spring Breakout

SARASOTA, Fla. -- There was an audible “Ooh” from the crowd at Ed Smith Stadium, and Carlos Lagrange quickly glanced beyond the right-field wall, checking the velocity of the pitch he’d just thrown in Saturday’s 5-4 Spring Breakout loss to the Orioles. It had registered in the triple digits, and

Bradfield dedicates Spring Breakout performance to late friend

SARASOTA, Fla. -- It was about more than playing in the national spotlight. More than the dinner bet placed with an old college teammate earlier in the month. More than a game. As Enrique Bradfield Jr. slid home to score a run during the first inning of Saturday night’s Spring