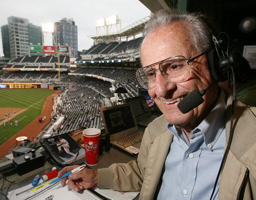

Padres Broadcaster, Jerry Coleman, has Passed Away

Jerry Coleman, a two-time war hero who became one of the most endearing figures in Padres history, passed away Sunday afternoon at the age of 89.

Coleman died at Scripps Memorial Hospital with complications of head injuries he'd suffered in a fall last month. Coleman had been in and out of the hospital since the early-December fall, according to several of his close friends, and also contracted pneumonia.

Gerald Francis Coleman, born Sept. 14, 1924, in San Jose, Calif., wore the Padres uniform for only a year. At that, it was a fairly desultory year for all concerned - and yet his jersey number is one of few retired to the franchise's wall of fame.

In 42 years as broadcaster of Padres games, Coleman became the link between the major league team and San Diego. To many, he was its very identity.

Coleman was as beloved for his favorite-uncle voice as Hall of Fame player Tony Gwynn was for his line drives between short and third. Coleman's mistakes and misspeaks, much as he had to swallow his annoyance at their too-frequent re-hashing, made him even more of an icon of the community.

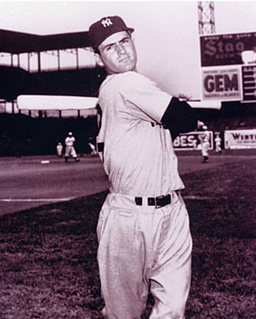

Coleman's humility and self-effacing ways belied an extraordinary personal history of courage, sacrifice and accomplishment. Addressed affectionately and respectfully at the ballpark as "The Colonel," he was a Marine Corps aviator in both World War II and the Korean War. And he was an All-Star second baseman for the dynastic New York Yankees who once was Most Valuable Player of a World Series.

"Jerry Coleman was a hero and a role model to myself and countless others in the game of baseball," Commissioner Bud Selig said in a statement released Sunday. "He had a memorable, multifaceted career in the national pastime -- as an All-Star during the great Yankees' dynasty from 1949-1953, a manager and, for more than a half-century, a beloved broadcaster, including as an exemplary ambassador for the San Diego Padres.

"But above all, Jerry's decorated service to our country in both World War II and Korea made him an integral part of the Greatest Generation. He was a true friend whose counsel I valued greatly.

Major League Baseball began its support of Welcome Back Veterans to honor the vibrant legacy of heroes like Jerry Coleman. Our entire sport mourns the loss of this fine gentleman, and I extend my deepest condolences to his family, friends, fans of the Padres and the Yankees, and his many admirers in baseball and beyond."

That Coleman won over so many people in the relatively unseen realm of a radio booth hid the fact he was an unfailingly dapper gentleman. While his time on the air was decreasing over the past few years, the testimonials mounted and honors culminated with Coleman's receiving the Ford C. Frick award for his work behind the microphone from the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2005.

"Bottom line: People loved Jerry and respected him, because you could tell from listening to him what a wonderful person he was," said Vin Scully, the legendary voice of the Dodgers for 65 seasons. "I considered it a great privilege for me to be one of those who voted for Jerry's induction into Cooperstown. What an amazing life."

Before he ever played major league baseball, Coleman was a World War II bomber pilot with 57 missions flown in the Pacific theater. Only a few years into his big-league career, he returned to the Corps and combat, flying another 60 missions over Korea and surviving a horrific crash.

Not given to flashiness in either his infield play or his personality, Coleman was overshadowed by the likes of Joe DiMaggio and roommate Mickey Mantle on some of the most vaunted New York Yankees teams of all time, yet he was hardly without distinction of his own.

He was the American League's Rookie of the Year in 1949 - and the AL's top fielding second baseman that year - and MVP of the World Series the next year, when he set a Yankees record for double plays by a second baseman with 137. Batting a respectable .275 in six World Series, Coleman helped the Yankees win four of them.

"Jerry was one of the nicest men ever in the game and one of the smartest players, too," said Don Newcombe, a former Dodgers pitcher who struck out 11 Yankees in Game 1 of the '50 World Series. "He was not the greatest second basemen ever, but one of the smartest. He wasn't a brilliant player in the showy sense, but brilliant in the intelligence sense.

"That's what made him a Yankee for so long. You had to be smart to stay on the field with those guys. You had to be smart to be the other half of the double-play combination with Scooter (Phil Rizzuto)."

If ever a player looked like a Yankee should look, too, Scully said that was Coleman.

"Jerry was a crisp and clean player," he said. "He looked the same in his Yankee uniform as he did in his military uniform. He had a look of great precision. He played his position the same way."

Military service interrupted - and perhaps abridged - what had been a promising playing career. Coleman followed his terrific rookie season with an All-Star year in 1950, boosting his average to .287 while driving in 69 runs, even though he generally batted second or eighth in the Yankees' batting order.

"Jerry was there for a reason, because he knew how to hit behind Rizzuto," said Newcombe, "and because he thought nothing of doing it because he was so unselfish and such a great team man."

Same as Ted Williams, Coleman left baseball a second time and reported for duty in the Korean Conflict. Before it was over, he had earned two Distinguished Flying Crosses, 13 Air Medals and three Navy Citations.

"There were times," Coleman said, "when you were up there and realized that all you were doing was practicing death."

He flew a Corsair on bombing runs over North Korea, often operating at night without running lights on radio blackout. Coleman told of a harrowing night sortie in which his vision was further impaired by oil leaking all over his windshield. Opening his hand-cranked canopy, Coleman lost his headset to the wind, essentially rendering him deaf, dumb and blind while negotiating the hills.

"He's flying a plane loaded with bombs in the pitch black and his oil gauge is dropping," said longtime broadcasting partner Ted Leitner, adding that it was only with intense prompting that Coleman would share his wartime travails. "Being a typical Marine, he decided to complete his mission and hope he had enough oil to finish. He got his plane down. Just imagine, though, living with the thought of getting shot out of the sky every day."

Headed out on another mission, Coleman's plane had risen just 100 feet when the motor died. Instead of unloading the bombs on the airstrip below, putting military personnel at risk, Coleman crash-landed the jet with the knowledge that the bombs most likely would detonate upon impact.

They didn't, but Coleman's plane flipped over. The straps of his crash helmet were suffocating him as he was pulled from the wreckage, whereupon a Navy corpsman revived him.

"To him, the Marine Corps was No. 1 after family," Leitner said. "This is a guy who wore the pinstripes at Yankee Stadium, who roomed with Mickey Mantle, who had his picture taken with Joe DiMaggio, who played in World Series and was MVP of one of them. Yet he'd tell you that his time with the Marines was more important to him. Nobody shot at him at Yankee Stadium."

Yet his return from war to the diamond gave him some anxious moments. Discharged in September 1953, he was feted at Yankee Stadium on "Coleman Day." Coleman said he was "terrified" by the focus on his return.

"Don't bother goin' out to talk to him," manager Casey Stengel said in the New York Times account of the occasion. "He's so scared he won't even know you. He didn't even know me this mornin' and he sure was here early enough, 'bout 8 o'clock, I'd say. By 11 he sez to me, 'Gee, Case, only three hours to go.' You'd think they wuz gonna guillotine him or somethin'."

Broadcasting seemed a natural transition for Coleman, easygoing and quick-witted, but it didn't happen until three years after his retirement in 1957. He spent three years in the Yankees' front office before he was offered a shot at television, where he made his debut on no less than the CBS Game of the Week with Dizzy Dean and Pee Wee Reese. (Dean, incidentally, was among the eight other broadcasters beaten out by Coleman for the Frick Award.)

The Yankees lured him back as a broadcast-booth teammate to Mel Allen, Red Barber and Rizzuto in 1963, and seven years later he moved west to host the California Angels' pre-game show and anchor sportscasts on KTLA-TV.

The Padres were loaded with ex-Dodgers and ex-Angels, most brought down by Buzzie Bavasi, who had run both clubs and started the expansion franchise in San Diego. Coleman arrived here in '72, continuing to call the national CBS Radio Game of the Week for 22 years.

"I listened to Jerry do Yankee games when I was a kid, and then I'm in the booth with him, so you can imagine what that meant to me," said Leitner, who worked with Coleman for decades. "You'd hear him talking about today's players, how different they are, but you'd never hear him say 'In my day ...' He was not a live-in-the-past kind of guy.

"Don't get me wrong. Some of that modern-ballplayer stuff drove him crazy. But I never saw him lose his temper in 26 years, never saw him explode at something somebody did. I never heard him say 'That's dumb!' - and he could have said that to me 100 times a day."

Coleman borrowed the catch-phrase "Oh Doctor!" from Red Barber and Casey Stengal. It became his signature as well in San Diego, the one splashed across banner headlines when the Padres finally won a pennant in 1984. Whenever a Padres fielder made a tough play, heads in the ballpark turned backward to see if Coleman would "Hang a Star" on the glovework or a great throw.

"Back in grade school, we had a spelling test every Friday," Coleman said. "If you got all 20 right, you got a gold star. I never got a gold star."

Invariably, alas, references to Coleman's broadcasting got around to some of the descriptions that didn't quite come out right. "Colemanisms," they came to be known, and not just locally.

"He laughed them off, but he hated the living hell out of the malaprops and the attention they brought him," Leitner said. "I mean, he hated them. He'd go to Milwaukee and they'd do a 'Who am I?' thing on the scoreboard, then play a malaprop of Jerry's. That embarrassed him. Who wouldn't be embarrassed? For the longest time, too, I think it might've kept him out of the Hall of Fame.

"People are always rattling off Colemanisms to me. I say 'Look at the sum of the man.' When you think of everything else the man was about, the things he did in his wonderful life, who gives a bleep (expletive) if he misspoke?"

It was with both empathy and sympathy, but also disappointment, that Scully recalled how the mistakes followed Coleman everywhere.

"The malaprops mean nothing," Scully said. "You spend 3 1/2 hours every day talking and you hear everything coming out of your mouth. But what we do is like skywriting. You put it out there, but then it soon blows away."

Peers found humor in Coleman's play-by-play writing. Before his own death in 2011, Duke Snider recounted with great relish the story of how former Dodgers teammate Don Drysdale, also trying to parlay his playing success into a broadcasting career, joined Coleman in the booth and studied the way Coleman filled out his scorebook during games.

"Don said he understood everything Jerry wrote in the book, all the different marks he made and what they meant, except one," Snider said. "There were a few at-bats where Jerry'd written 'WW' and Don kept wracking his brain, trying to figure out what 'WW' meant. Finally he asked and Jerry said, 'Wasn't watching.'/i"

Scully said he remembered Coleman as not only a friend and colleague, but as a guest, one of the best he ever had. The occasion was a Memorial Day tribute.

"Jerry talked about flying in Korea and his plane being in trouble," said Scully, "how when one plane was struggling, all the fellows in the other planes would listen in and send up their prayers for the plane in trouble. It was a beautiful thing to hear about, a beautiful show, and he was ideal in the telling of it."

Decades after he flew his first raids on the Solomon Islands, though, the telling of those stories never got any less painful.

"Memorial Day was tough on him," said former Padres play-by-play man Mel Proctor. "On Memorial Day, he'd get a tear in his eye. Jerry volunteered great baseball stories, but very few war stories. It was too hard for him."

Conversely, Coleman's military experience and appreciation for those in the service made him special in the eyes and ears of San Diego baseball fans, so many of them either active duty or retired.

"San Diego was the perfect town for him, in a lot of ways," Leitner said. "If he was in New York and had those malaprops, the press there would've treated him like a serial killer. San Diego's not like that. He was the guy who taught a lot of San Diegans their baseball. They respected him and didn't care about the way he said things sometimes."

Then again, all too often, Coleman was trying to describe plays made by players who were tripping over themselves. The Padres teams of the 1960s and '70s were largely wretched, more often than not placing last in the NL West and failing to finish higher than fourth until 1984.

The franchise became known for bizarre stuff, like owner Ray Kroc grabbing the public-address microphone, criticizing his team's play for the crowd and ordering security to get a hold of that naked streaker running around the field. Kroc's decision to make Coleman the Padres' manager - without any coaching experience whatsoever - in 1980 was considered just another bit of silliness.

"We started out last on Opening Day and we held that position all year long," Coleman once said. "People say, 'You guys had three Hall of Famers on that team (Ozzie Smith, Dave Winfield and Rollie Fingers).' True enough. Except the other 20-some guys couldn't play."

For what it's worth, Coleman guided the Padres to their second-best season to that point, a 73-89 mark.

"I don't think he really wanted to do that," said Tom Lasorda, who was manager of the Dodgers at the time. "He could've been a good manager, though, if he'd had a real opportunity to do it. Jerry was a great ballplayer, an intelligent player, and he was a goddam bomber pilot. With those qualifications, you think he couldn't have been a good manager, too?"

"Jerry's the best," said Proctor, "one of those special people you thank God you got to meet."